The Begum’s Millions

The Begum’s Fortune

Les Cinq cents millions de la Bégum (1879)

Member Andrew Nash’s website contains all the English variations of this title.Plot Synopsis:

(courtesy of member Dennis Kytasaari’s - website)

Dr. François Sarrasin, a Frenchman, and a German named Professor Schultze are the sole heirs to a fortune of 525 million francs left by their mutual relative, a deceased Begum of India. With his half of the fortune, Dr. Sarrasin builds an ideal community called Frankville in the northwestern section of the United States. Professor Schultze uses his half of the money to construct his own city called Steeltown, where the main output of the city is weapons of destruction. Schultze’s real intent with Steeltown is to see to the destruction of Frankville.

Review(s)

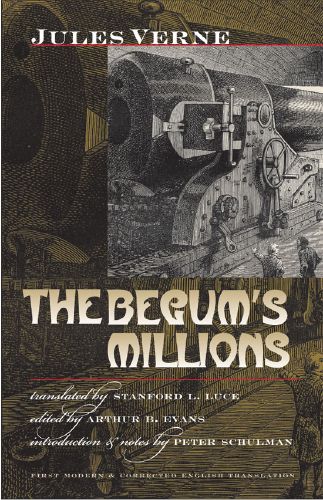

The Begum’s Millions (Early Classics of Science Fiction)

Translator: Stanford L. Luce. Introduction & Notes: Peter Schulman; Editor:

Arthur Evans. Middletown, CT, Wesleyan University Press, 2005. 308 pages, ?? ill.

Hardcover — ISBN-10: 0819567965, ISBN-13: 978-0819567963

RECOMMENDED (read why below) Get it

at Amazon.com.

Jules Verne is, after Agatha Christie, the most popular writer in the world. Neither

— until recently—has ever gotten much respect from the academic or critical

establishment. What they share, along with some warm-hued period coziness, is a

gift for absolute storytelling, for making a reader want to keep turning page after

page to see what happens next. Christie does this through her mastery of plotting—not

only eventually revealing “who done it” but, better yet, how it was

done. Verne’s strength can be elicited from the overall title he gave his

works, “Voyages Extraordinaires.”

To begin to understand his narrative magic, simply call to mind any of the best

known Verne titles, of more than 60: A Journey to the Center of the Earth

(1864), Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (1869-70), Around the World

in 80 Days (1873), The Mysterious Island (1874-75). These are

all tales of marvels and monsters or eyewitness accounts of realms from which no

traveler has ever returned, till now. Verne (1828-1905) lived through the great

heyday of colonial expansion and global exploration. Back in Birmingham and Lyons,

industry and technology were also busily developing new forms of transportation,

communication and destruction. So Verne’s fiction neatly, imaginatively joined

the wonders of geography to those of the foundry and the laboratory, without neglecting

an enlivening breath of the sublime or the fantastic.

Indeed, long before Hollywood discovered computer graphic imaging, the books of

Jules Verne provided the 19th-century equivalent of industrial light

and magic. Verne’s brisk, clear prose deftly mixed the real and the almost

real, often by employing a fact-filled style that was sometimes journalistic, at

other times scientific, but always replete with news items, historical events and

leisurely descriptions of how things worked. As a result, the reader, especially

the youthful [reader, not only marveled, “Can such things be?” but might

also murmur, “I wonder if I could build one of those myself?” Little

surprise, then, that Werner von Braun, Robert Goddard, astronaut James Lovell and

many other pioneers of the space effort testify that From the Earth to the Moon

(1865) first set their imaginations soaring upward.

Still, Verne’s work has suffered three grievous literary misfortunes. First,

it was badly translated into English, occasionally bowdlerized and sometimes actually

rewritten. Second, it was largely relegated to the children’s bookshelf, even

though Verne aimed for an audience of all ages. Third, much of the late and posthumously

published fiction was written either entirely or in large part by Verne’s

son Michel, who blithely signed his father’s lucrative name to the title page.

Such cavalier publishing practices soon created the common image of Verne as a sloppy,

tin-eared writer for the semi-literate.

It probably didn’t help that he was also soon dubbed the father of science

fiction (Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley being the mother). In fact, Verne’s books

are more accurately what he himself called “novels of science,” and

many are essentially realistic travelogues to distant lands, or even ludic, experimental

texts (like the 1899 Will of an Eccentric, in which the human characters

are all players in a kind of Monopoly game using the United States itself as the

board. No wonder that some of the most innovative 20th-century writers,

such as Raymond Roussel and Georges Perec, look to Verne as an inspiration). Several

of the visionary writer’s more interesting later books even display despair

over what science might do to the world, as much as for it. Certainly, The Begum’s

Millions (1879) is best read as a cautionary political fable, part dystopian

satire, part Dickensian social tract.

A begum is an aristocratic Muslim woman—in this case, the widow of a maharajah,

who leaves a vast fortune to two European savants, a German scientist and a French

doctor. Each decides to set up an ideal community in the Pacific Northwest of the

United States. Kindly Dr. Sarrasin envisions a germ-free, sanitary city where public

health is the chief concern of the government. By contrast, Prof. Schultze wants

to prove the superiority of the “Saxon” over the “Latin”

by building a “City of Steel” devoted to the manufacture of weapons

of mass destruction. (He is obviously based on Alfred Krupp, the German munitions

king.) Eventually, Schultze declares that Sarrasin’s neighboring utopia must

be destroyed as an example to the world of German superiority and of his own unstoppable

technological power. To do this he constructs a super- cannon whose gigantic shells

deliberately break apart to rain down fire over vast areas. But he has, in reserve,

an even more insidious weapon: a special projectile filled with compressed liquid

carbon dioxide that, when released, instantly lowers the surrounding temperature

to a hundred degrees below centigrade, quick-freezing every living thing in the

vicinity. As Schultze proudly says, “thus, with my system, there are no wounded,

just the dead.”

Will this proto-Hitler succeed in his plans? Will he use his early version of the

neutron bomb? Opposing him, Verne gives us Marcel Bruckmann, an Alsatian whose natal

land is, after the Franco-Prussian War, under the dominion of Germany. But can this

young Theseus even gain access to Stahlstadt’s inner sanctum, the Tower of

the Bull, let alone slay its modern Minotaur?

In The Begum’s Millions, Verne presents his first truly evil scientist.

(Captain Nemo is a romantic anti-hero, with good reason for his depredations.) He

also announces a theme that will recur in his subsequent fiction: the potentially

dire effects of science on society. As early as the lighthearted Dr. Ox’s

Experiment (1874), a callous researcher transforms a placid village into

a raging cauldron of emotion by piping pure oxygen into homes and public buildings.

Every feeling is intensified, metabolisms are sped up, and an opera that normally

takes six hours to perform is zipped through in 18 minutes. In Master of the World

(1904), the once relatively thoughtful hero of Robur the Conqueror (1886)

returns as a megalomaniac who spreads shock and awe with his powerful battle station,

a combination tank-plane-ship-submarine called, simply, The Terror. Finally,

in The Barsac Mission (1919) -- announced as the last “Voyage Extraordinaire”—we

are taken to a fortress city in Africa, from which a criminal mastermind uses the

inventions of a brilliant, if blithely unaware scientist to wreak global havoc and

mayhem.

The Barsac Mission was completed by son Michel Verne, though it almost

certainly reflects

Jules’s increasingly pessimistic outlook. That despair reaches its acme in

the famous short story, also by both Vernes, “The Eternal Adam” (1910):

A scientist of the far future named Zartog Sofr-Ai-Sr is chastened to discover that

archaeological evidence reveals that the men and women of the inconceivably distant

past—that is, of our era—were intelligent, civilized and almost completely

wiped out when the oceans suddenly rose and totally engulfed the continents. There

is, concludes Zartog, no progress to history, only unending, senseless repetition.

Like some other prolific writers (Alexandre Dumas, Jack London), Verne himself occasionally

took over another man’s plot (duly paid for) and reworked it to fit his own

obsessions and standards. Thus, The Begum’s Millions builds on a

story originally drafted by a prolific hack named Andre Laurie (who eventually gave

the memorial address at Verne’s funeral). All these and many other fascinating

matters are discussed in the scholarly apparatus accompanying this handsome edition

of this surprisingly dark (and prescient) novel: Peter Schulman’s introduction

fills in the historical and interpretative background, while Stanford L. Luce’s

“modern and corrected” translation is overseen by the eminent Verne

authority Arthur B. Evans. What’s more, The Begum’s Millions

is only the latest offering in Wesleyan’s admirable “Early Classics

of Science Fiction” series, which also includes Verne’s Mysterious Island

and the less familiar Invasion of the Sea (1905) and The Mighty Orinoco

(1898).

To read Jules Verne is one of the great treats of childhood. To read Jules Verne

later in life is to discover a writer just as satisfying but even richer, one who

is not only a natural storyteller but also a mythmaker, a social critic and an innovative

artist. In France, Verne is now studied as a major literary figure, and thanks to

fresh translations—from Penguin and university presses at Indiana and Nebraska,

as well as Wesleyan—more and more of his work is available to American readers

in reliable texts. Give The Begum’s Millions or one of the other novels a

try this winter. There’s a lot more to Jules Verne than what you find in those

old, albeit quite wonderful, Disney movies.

© 1993 - 2026 North American Jules Verne Society, Inc. — a 501(c)(3) Corporation

© 1993 - 2026 North American Jules Verne Society, Inc. — a 501(c)(3) Corporation